In late 1991, economic disturbance, problems in accessing fuel heating issues, and calls for democratic freedoms, ultimately led to the disintegration of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) by December 1991. Many people sought to assist Russia people in their activism against the USSR by sending messages for them using facsimile systems, when the Soviet Union was monitoring voice telephone services. It was a small help, but it showed a snapshot of how information sharing could make a huge difference in world events. Two years later, the global information environment would radically change the world, with public accessibility to “the Internet” or more accurately to the World Wide Web (WWW).

To be clear, the Internet is NOT the World Wide Web (WWW). The terms are used interchangeably in 2022, but that is totally wrong and it is an important error to understand not just today and tomorrow, but also where we came from a very short time ago. The Internet is the network backbone. The “Internet” really began as a research project in 1969. But the obscure scientific and library systems had no real relevance to most of the world, nor did the 1991 Minnesota library “gopher” system. The breakthrough of World Wide Web graphical browser systems in 1993 is the key milestone.

Many have come to believe that the WWW that is widely (and incorrectly) called the “Internet” is one ubiquitous online service, when in fact, that is a choice, and has been an uncertain choice over the past 30 years. There are those, from many different perspectives, who are not interested in one “Internet,” but in many different “Internets” each of which protects their world view. So we have come from dial-up modems connecting cyber pioneers to a global Internet, and now those advocating for a “Splinternet.”

In the early 1990s, there were a few major Internet service providers, Delphi, CompuServe, GEnie, and AOL. Delphi started providing national consumer access to the Internet in 1992; its main services were email (July 1992), FTP, Telnet, Usenet, text-based Web access (November 1992), multi-user games (MUDs), Finger, and Gopher. Another that year was the Rockville, Maryland-based GEnie (General Electric Network for Information Exchange) which began offering RoundTable Bulletin Board Systems (BBS). AOL offered its proprietary system in 1991 with AOL for with a GeoWorks interface, and in 1992 provided an AOL for Windows interface, then expanded its proprietary email service in 1993. In 1992, CompuServe hosted the first known WYSIWYG email content and forum posts, and created a CompuServe Information Manager (CIM) system. At one point, only a limited number Internet service provider companies existed and a series of dial-up amateur BBS sites. But in 1993, with the development of the WWW browser, all of this would change.

Less than 30 years ago, 1993 was a key year in the development of the Mosaic browser, which would then lead to the Netscape browser. These provided tools to allow a global user community to access the WWW, which gave them real access to the Internet. The Mosaic browser was initially only for UNIX computers, which discouraged many early users. But the next year, in 1994, the Netscape browser would be provided by the creator of the Mosaic browser. Netscape Navigator would be the tool that would become access to the WWW for the world, and would be integrated into Internet Service Providers and computers of every kind.

The WWW, what most users consider to be “the Internet,” is a series of interfaces using HyperText Markup Language (aka “HTML”), which is the standard markup language for documents designed to be displayed in a web browser. The creation of the idea of a Uniform Resource Locators or (URL) to create “web address” on the WWW was developed and refined in 1993 and 1994. These were led by Tim Berners-Lee.

In 1993, I had a poster map of the Internet World Wide Web (WWW) major sites on my office wall in Arlington, Virginia. There were about 30 WWW major sites on the map. CERN reported that “in November 1992, there were twenty-six websites in the world.” It is estimated that website numbers have changed from 30 websites in 1993 to 1,900,000,000 websites in 2021 (likely an underestimate).

Other web browsers were developed to compete with Netscape Navigator (and Netscape’s creator went on to create the Mozilla Firefox browser in 2004). In January 1995, “Jerry and David’s Guide to the World Wide Web” became the browser known as “Yahoo.” By August 1995, Microsoft developed a browser called “Internet Explorer” as an add-on to its Windows 95 operating system. By the end of the 20th century, Stanford University students changed their “BackRub” browser algorithm to a prototype of a browser called “Google Search” by the end of 1998. There are now an estimated four billion users of Google Search.

Just as important, the end of the 20th century also saw the development of two other international Internet changes for web browsing. While WWW URLs were being developed, Internationalized URLs were also being developed, using Internationalized Resource Identifier (IRI) of unicode letters for international domains. This allows URLs for WWW browsing in languages OTHER than English or English ASCII characters. This also led to the development of Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). The first international domain name was in Chinese in 1999 for Taiwan.

In 1996, a Chinese software engineer developed the RankDex browser, which then became the Baidu browser in 2000. There are now an estimated one billion users of the Baidu browser, which is rapidly increasing as China’s population becomes more digitally active on computer networks.

In the late 20th and early 21st century, Internet functions included the development of “weblog” (or “we blog” based on Ian Ring’s first 1997 web journal called “blog”) sites for people to share information outside of structured Internet web pages, and with more “live” information regularly shared. These weblogs became popular sources of news and information. And in the early 21st century, they were complemented by “microblogging” sites, or what people today would consider “social media.” Microblogging sites such as Twitter (July 2006), Facebook (February 2004), Tumblr (February 2007), were intended to share events and images, but then also became tools to share information, news, opinions, and then to actively shape public opinion. The photo-sharing application (“app”) called Instagram, began as a web app called “Burbn” to share the software engineers love of whiskey and bourbon alcohol. In 2010 it was relaunched as “Instagram,” for photo sharing. It can be used for microblogging, but that was not the original intent.

Such microblogging was also being created in China, and all of the microblogs are called “weibo.” Sina Weibo is the most popular weibo (launched August 2009). Chinese language idiom-based scripts allow for a greater number of “words” in microblog messages than Western language lettering. The Sina Weibo has a 2,000 character limit in posting (compared to the 280 character posting in Twitter posts). As of 2020, it’s impossible for anyone outside China to register an account on the Sina Weibo platform. Other weibos have included: Digu, Fanfou, and weibos for Chinese media. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has required strict controls and censorship on these weibos.

Censorship is not unique to China and/or the CCP, but it is a matter of degree and level. All microblogging systems and commercial Internet service providers (including the earliest Internet service providers, e.g., AOL) have had various rules and/or “Terms of Service (TOS),” which have provided guidance on what is and what is not acceptable internet communications. The difference is a matter of degree and intention. Early censorship was designed to protect users from abuse, threats of violence, etc., whereas later censorship efforts have focused on shaping opinions, narratives, and what was/was not considered “misinformation.” Furthermore, efforts to ban and/or punish other nations using digital services have also led to a further fractionalized (or “balkanization”) of Internet service usage, especially on microblogging sites based on view and opinions. While this was a core function of the CCP Communist China controls over their weibos, such censorship is not exclusive to CCP Internet usage.

Simultaneous to the USA Internet development, while much slower, there was also Internet development in Russia. One of the first breakthroughs was in April 1995, with the creation of the website “Uchitelskaya Gazeta,” and two years later in September 1997, there was the launch of the Yandex search engine (www.yandex.ru). In January 2001, the Ru-Center in Russia became the first Russian language-based Internet domain registration organization. In 2007, SUP Fabrik licensed the use of the LiveJournal brand in the Russian Federation and the service of users writing in Cyrillic for microblogging. There are now 6 million Russia domain websites in the .RU and/or .RF domain names. In October 2006, the VKontakte (VK) social networking site was created in Russia for messaging and social network communications; it is the most popular site in Russia. It is followed by VK’s Odnoklassniki site. In 2012, Mail.ru portal created a Futabra microblogging site, but it did not last a year before it closed.

In Russia, due to foreign registars refusing Internet domains for Russian users, the Russian Ministry of Digital Development is having recommending that administrators of domains in the .RU zones move to hosting and registrars based in Russia, and is providing free Russian TLS/SSL certificates (Yandex and Atom) to organizations (like Russian banks), whose security certificates were revoked by foreign certificate authorities. Internet restrictions are making the Russia Internet focused on its own autonomy and self-sufficiency. There is an increasing “Russia Internet” (“Runet), which is based on using Russian language, including Russian language online shops, Russian search engines, email services, anti-viruses, dictionaries, etc.

While China already had alternatives to the USA-based Twitter and microblogging in place, India and India began working on their own alternatives to microblogging sites beyond the USA’s Twitter controls and limitations. In January 2015, India-based ShareChat started microblogging in India and worldwide, which prohibits English language content. In November 2019, India developed Koo (formerly Ku Koo Ku) is a multilingual Indian microblogging and social networking service, based in Bengaluru, India.

The concept of world trade and openness in global communication is a concept that is less than 30 years old. The creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995 is a relatively “new” global phenomenon. Many have assumed that this path of globalization would be the only path for the future.

But in Internet communications and exchange of information, we have been seeing a growing “balkanization” of information both within countries and between countries. When this comes to actual differences in Internet services in different regions or countries, this is being termed as a “Splinternet.” The Decentralized Information Group at MIT considers a “Splinternet” as an information system “ecosystem” where people have completely different sets of information on local events, world events, and view of reality. As people with different life and political views migrate to different social media microblogging sites to share views of those like themselves, will such “splinternet” also lead to some nations “unplugging” from the “global Internet” and creating their own systems? Or is that already happening?

The co-lead of the Decentralized Information Group at MIT was Tim Berners-Lee, who was the original creator of the WWW and URLs used to access our shared Internet web. Tim Berners-Lee also began working on the MIT’s “Solid Project” to change the way Web applications work, and allow better control over data ownership in various cloud “pods” with a unique ID, as part of work with the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C).

The idea of only “one Internet” with one set of domain controls, etc., is still an idea that is rooted in the late 20th century and its optimistic “one world” perspective. However, as we see with various cultures both within nations and between nations, there is the sense by many of a lack of fairness and equity in universal human rights of freedom of expression. There is a belief that different Internet services, media, social media, will focus on only one facet of the reporting as a “narrative” and purposefully and/or unconsciously leave out other aspects of such reports. Inconsistency among Internet service and microblogging social media on rules and standards fuels such concerns and adds to the belief of the need for division of Internet communications.

The MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy (IDE) references a Kearney Global Business Policy Council on concerns regarding “digital disorder.” In MIT’s description of this capitalist organization’s views, MIT states: “a global battle for technological supremacy in the 21st-century digital economy is heating up, raising the risk of competing technological standards and creating the potential for an ‘islandized’ digital environment. Altogether, these actions are creating a digital disorder that is becoming more difficult for companies to navigate.” “The Internet is full of fake news, leading to increased divisions and fading trust in governments, business and just about all other institutions. Around the world, consumers particularly distrust foreign technologies and companies, forcing digital platforms to stick primarily to their home markets and fragmenting the overall global digital environment.”

But just as Communist-led nations view the world through their filter, the Capitalist-led nations also view the world from their filter. In either case, will centralized controls over the Internet continue or will the growth of globalism invariably lead to a “Splinternet”?

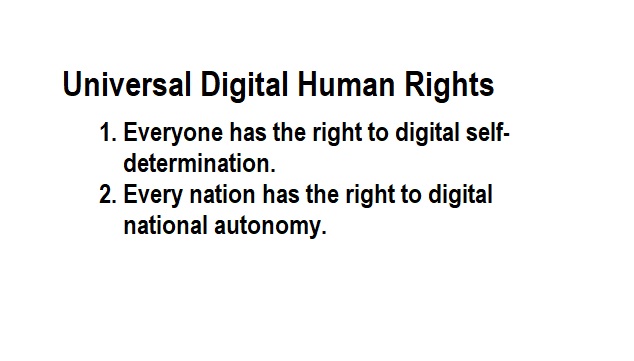

From the USA-based leadership, will that leadership eventually migrate from respect to bitter resentment? Do billions of people around the world not have the right to their own “digital self-determination” in the same way we defend their “national self-determination”? Must the people of the world be guided by USA-based Internet organizations, USA media using the Internet and microblogging, and USA-based microblogging organizations to define how people around the world should think, what they should believe, and what they have they have right to say as part of the universal human rights of Freedom of Expression?

Or is digital growth also freedom? Digital self-autonomy? And for other nations, whether USA leadership likes it or not digital self-determination?

In the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), we recognize in UDHR Article 15 that “everyone has the right to a nationality.” Will we need to recognize such rights to include digital national autonomy?